Western liberal democracy seems to be in the grip of a momentary madness, or so the story goes. All across the West, publics we might have hoped were evolving in linear fashion into more perfect democratic citizens have “suddenly” been overcome by a “wave” of “far-right” fervor. They bristle with nationalism and anti-globalism, xenophobia, and isolationism. There are calls to ban immigration, to deport “illegals,” and to abandon asylum obligations. Migrants and refugees are seen as threats to national security: as terrorists in waiting or in the making. Significant public resources are to be diverted to their surveillance and to thwarting the evils they would otherwise surely perpetrate, Beyond their depiction as “the enemy within,” they are deemed an existential threat to culture and national identity, competitors for jobs, and a brake on national prosperity. Leaders are exhorted to favor their own countrymen over “aliens” and outsiders, and to shield them from the brutal forces of global trade with protectionism.

These unexpected public demands seem to travel with an angry rejection of the leaders and institutions that pulled these “politically incorrect” options from the policy menu. There is a fundamentally anti-democratic mood afoot that has lost patience, in particular, with the strictures of political correctness. In these conditions, formerly reviled parties and movements that once languished on the fringes have become viable acceptable if not quite respectable. The newfound popularity of these parties — some with past or present ties to Nazi ideology — is fueled by perceptions that the political mainstream has lost touch with those they are meant to represent. “Self-serving” political elites, leaders viewed as remote from regular folk but “pandering” to minorities, seem to feed into a growing sense that “this is not my government” and “these are not my people.” This may well be the animating spirit at the heart of what has come to be called “far-right populism.”

While the origins of these developments are open to question, the purported outcomes have unquestionably been shocking to many. Donald Trump ascended to the American presidency. Partisanship and ideology aside, it is hard to imagine that Trump's temperament and experience equip him for leadership of the free world. Britain voted to

176 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

exit the European Union in a history-changing referendum. And the French flirted dangerously with Le Front National. While (to many commentators’ palpable relief) Marine Le Pen was ultimately held to “just” 35 percent of the presidential vote, this can be seen as a victory over far-right populism only compared with what might have been. The same can be said regarding the recent performance of the Freedom Party's Norbert Hofer in Austria’s presidential election. In both cases, the far-right populist candidate came close to winning the presidency of a major Western nation, and note, in neither case facing off against a contender from the traditional “left” or “right.” Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom was blocked from the Dutch governing coalition, despite placing second, only via the determined collusion of all his mainstream opponents. Recent general elections in Germany and Austria have likewise seen a marked “populist” surge that upended “normal” politics. Whatever these political brands might once have represented, “left” versus “right” is being overturned in a new game of “insiders” versus “outsiders” . . . or so it seems.

So what is this far-right populism? And where has it “suddenly” come from? From its alleged suddenness, many analysts have arrived at explanations that are redolent of sudden ill health, By this account, far-right populism is a momentary madness brought on by recent environmental stressors (the global financial crisis, the decline of manufacturing, the inevitable dislocations of globalism) and exploited by irresponsible leaders who deflect the patients’ anxieties onto

177 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

easy scapegoats (migrants, refugees, terrorists) for their own political gain. Central to this diagnosis is the notion that the patients’ fears are irrational and can be alleviated by more responsible treatment and the reduction of stress (by boosting the economy or increasing social supports). With appropriate interventions and the removal of toxic influences, it is thought that our populists will eventually “snap out of it” and come back to their senses.

The social scientific literature on populism crosses many disciplines, and the concept is frequently and casually deployed in both academic and popular commentary. We cannot do justice to it here. Many accounts converge on the idea that populism is a kind of “zeitgeist” in which the pure/real/true people are seen to be exploited by a remote/corrupt/self-serving elite (e.g., Mudde 2004: 560). In what is perhaps the most explicit and detailed definition, populism is seen as “pit[ting] a virtuous and homogenaeous people against a set of elites and dangerous ‘others’ who are together depicted as depriving (or attempting to deprive) the sover eign people of their rights, values, prosperity, identity, and voice” (Albertazzi and McDonnell 2008: 3). From our perspective, the addition of these details — regarding the good ness and sameness of the ingroup, and the outgroup’s intent to undermine their values and identity — serves mostly to reinforce our sense that populism per se is really more “zeitgeist” than political ideology or enduring predisposition On its own, it seems to us more a complaint about the cur rent state of the world (a perception of contemporary conditions) rather than a vision of the good life. It gains substance

178 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

and meaning only when fleshed out and prefixed by something else, like far-right populism: what Mudde and Kalewasser (2017) would call a “host ideology.” Only then do we know both what our populists actually want (virtue and homogeneity: the one right way for the one true people) and how they presently feel (that elites and dangerous “others” are thwarting those desired ends).

Broken down in this manner, we can see that the present phenomenon of far right populism fits easily into the framework of a “person-situation interaction” that is at the heart of social psychology. ‘This is the notion that Behavior is a function of the Person (stable personality and enduring traits) interacting with their current (ever-shifting) Environment: B = f(P, E).* (use for 'function' ƒ ? - also 'em' for the formula) More pointedly, it is neatly encompassed by an interaction that Stenner (2005) labeled the “authoritarian dynamic”: intolerance of difference = authoritarian predisposition x normative threat. In this essay, we contend that the political shocks roiling Western liberal democracies at present — which in reality began with rumblings in the 1990s — are more appropriately and efficiently conceived as products of this authoritarian dynamic.

In the opening paragraphs of this Paper, we took care to draw out two distinct but seemingly entangled components of the current wave of far-right populism. These were (i) a multilaceted demand for less diversity and difference in society (the “far-right” component: a particular conception of the

179 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

good life) and (ii) a critique of the faithless leaders and institutions currently failing to deliver this life (the “populism” component), presumably due to their political correctness and fidelity to values remote from what The People actually want. Tangled up together, the two components fuel the populist fervor that now besets the West. From the perspective of Stenner’s “authoritarian dynamic,” this “far-right populist” tangle simply represents the activation of authoritarian predispositions (in the roughly one-third of the population who are so inclined) by perceptions of “normative threat” (put most simply: threats to unity and consensus, or “oneness and sameness”). The predictable and well-understood (not sudden or surprising) consequences of activating this authoritarian dynamic — of “waking up” this latent endogenous predisposition with the application of exogenous normative threat — are the kinds of strident public demands for greater oneness and sameness that we now hear all around us. Stenner explicitly noted that the theory of the authoritar ian dynamic was intended to explain “the kind of intoler ance that seems to ‘come out of nowhere, that can spring up in tolerant and intolerant cultures alike, producing sudden changes in behavior that cannot be accounted for by slowly changing cultural traditions” (Stenner 2005: 136).

In the remainder of this paper we will outline the theory of the authoritarian dynamic, briefly review available evi dence, and then examine whether this alternative account provides a more compelling and simpler explanation of pop ulism across the seemingly diverse cases of Trump, Brexit, and the National Front. We take advantage of an extraordinary

180 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

data set collected by EuroPulse in December 2016 that gives us deep insights into voting for populist candidates and causes in the United States, Britain, and France.

Stenner (2005, 2009a) identified three distinct psychological profiles of people who are typically lumped together under the unhelpful rubric of “conservative,” and who tend to vote for candidates designated as “right-wing.” The latter is a largely content-free self-placement, whose meaning is inconsistent across cultures and times, On this so-called right wing of politics, Stenner distinguished between what she called “laissez faire conservatives,” “status quo conservatives,” and “authoritarians,” It is vital to keep this distinction in mind because it is only the authoritarians who show persistent antidemocratic tendencies and a willingness to support extremely illiberal measures (such as the forced expulsion of racial or religious groups) under certain conditions (i.e., normative threat).

Laissez faire “conservatives” are not conservative in any real sense. They typically self-identify as classical liberals or libertarians. They strongly favor the free market and are usually pro-business, seeking to thwart “socialist” or “left-wing” efforts to intervene in the economy and redistribute wealth. Psychologically speaking, they have nothing in common with authoritarians (Haidt 2012). Authoritarians —those who demand authoritative constraints on the individual

181 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

in all matters moral, political, and racial — are not generally averse to government intrusions into economic life. Empirically, laissez faire conservatism is typically found to be either unrelated to authoritarianism or else inversely related to it, and not implicated in intolerance or populism to any significant degree.

Status quo conservatives are those who are psychologically predisposed to favor stability and resist rapid change and un certainty. They are in a sense the true conservatives: the heirs of Edmund Burke. Status quo conservatism is only modestly associated with authoritarianism and intolerance, and only under very specific conditions. It tends to align with intolerant attitudes and behaviors only where established in stitutions and accepted norms and practices are intolerant. In a culture of stable, long-established, institutionally supported and widely accepted tolerance, status quo conservatism and authoritarianism will essentially be unhitched, and status quo conservatism will lend little support to intolerant attitudes and behaviors.

Contrast status quo conservatism then with authoritari anism: an enduring predisposition to favor obedience, con formity, oneness, and sameness over freedom and difference. Bear in mind that we are speaking here of a psychological predisposition and not of political ideology, nor of the char acter of political regimes. (Note also that we make no claims about the psychological predispositions of Donald Trump,

182 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

Marine Le Pen, or any other political leader. Authoritarianism is an attribute of the follower, not necessarily of the leader, and one does not need to be an authoritarian to successfully deploy authoritarian rhetoric and attract authoritarian followers.) Authoritarianism is substantially heritable (McCourt et al. 1999; Ludeke, Johnson, and Bouchard 2013) and mostly determined by lack of “openness to expe rience” (one of the “Big Five” personality dimensions) and by cognitive limitations (Stenner 2005); these are two factors that reduce one’s willingness and capacity (respectively) to tolerate complexity, diversity, and difference.

In contrast to status quo conservatism, authoritarianism is primarily driven not by aversion to change (difference over time) but by aversion to complexity (difference across space). In a nutshell, authoritarians are "simple-minded avoiders of complexity more than closed-minded avoiders of change" (Stenner 2009b: 193). This distinction matters for the challenges currently confronting liberal democracy because in the event of an “authoritarian revolution,” authotitarians may seek massive social change in pursuit of greater oneness and sameness, willingly overturning established institutions and practices that their (psychologically) conservative peers would be drawn to defend and preserve.

To avoid tautology with the dependent variables we are trying to explain — a problem that plagued earlier research on The Authoritarian Personality (Adorno et al. 1950) — Stenner (2005) usually gauges “latent” authotitarianism with a low-level measure of fundamental predisposition: typically, respondents’ choices among child-rearing values.

183 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

For example, when asked what qualities should be sencouraged in children, authoritarians tend to prioritize obedience, good manners, and being well behaved over things like independence, curiosity, and thinking for oneself. Pitting this “bare bones” measure of authoritarianism against any variety of “conservatism,” and the whole roster of socio-demographic variables — including education, income, gender, class, and religiosity — Stenner (2005: 133; 2009a: 152) has shown via the World Values Survey that authoritarianism is the principal determinant of general intolerance of difference around the globe.

Authoritarianism inclines one toward attitudes and behaviors variously concerned with structuring society and social interactions in ways that enhance sameness and minimize diversity of people, beliefs, and behaviors. It tends to produce a characteristic array of functionally related stances, all of which have the effect of glorifying, encouraging, and rewarding uniformity and disparaging, suppressing, and punishing difference. Since enhancing uniformity and minimizing diversity implicate others and require some control over their behavior, ultimately these stances involve actual coercion of others (as in driving a black family from the neighborhood) and, more often, demands for the use of group authority (i.e., coercion by the state).

184 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

In the end, then, suppression of difference and achievement of uniformity necessitate autocratic social arrangements in which individual autonomy yields to group authority. In this way, authoritarianism is far more than a personal distaste for difference. It becomes a normative worldview about the social value of obedience and conformity (versus freedom and difference), the prudent and just balance between group authority and individual autonomy (Duckitt 1989), and the appropriate uses of (or limits on) that authority. This worldview induces bias against different others (racial and ethnic outgroups, immigrants and refugees, radicals and dissidents, moral "deviants"), as well as political demands for authoritative constraints on their behavior. The latter will typically include legal discrimination against minorities and restrictions on immigration, limits on free speech and association, and the regulation of moral behavior (e.g., via policies regarding abortion and homosexuality, and their punitive enforcement).

Stenner’s theory of the "authoritarian dynamic" tells us exactly when authoritarianism does these things, making it a useful tool for understanding the current wave of populism. As noted earlier, the authoritarian dynamic posits that intolerant behavior is a function of the interaction of an enduring psychological predisposition with transient environmental conditions of normative threat. Stenner contends that in the absence of a common identity rooted in race or ethnicity (the usual case in our large, diverse, and complex modern societies), the things that make "us" an "us" — that make us one and the same — are common authority (oneness) and shared values (sameness). Accordingly, for authoritarians, the conditions most threatening to oneness and sameness are questioned or questionable authorities and values, e.g., disrespect for leaders and institutions, authorities unworthy of respect, and lack of conformity with or consensus in group norms and beliefs. This is what Stenner has termed "normative threat," or "threats to the normative order."

185 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

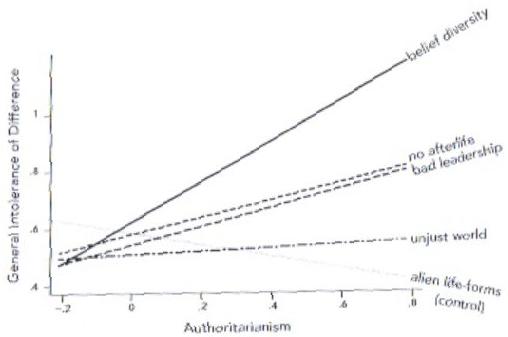

Stenner (2005) demonstrated the prevalence and significance of this authoritarian dynamic with many different kinds of data, showing that the intolerance produced by authoritarianism is substantially magnified when respondents:

186 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

In every case, normative threat dramatically increased the influence of authoritarianism on general intolerance of difference: racial, political, and moral. The latter constitute the authoritarian's classic "defensive arsenal," concerned with differentiating, defending, and glorifying "us," in conditions that appear to threaten "us," by excluding and discriminating against "them": racial and ethnic minorities, immigrants and refugees, political dissidents, radicals, and moral "deviants." Notice that the activation of the authoritarian dynamic by collective threat in one domain will typically boost the display of these classic attitudes and behaviors across all domains. Thus, should fears about Muslim immigration activate authoritarian predispositions, this will usually provoke authoritarians to a whole panoply of sympathetic "vibrations," which might include strident demands to limit rights and protections for "domestic" racial/ethnic minorities, to restrict free speech and assembly, and to deploy state authority to write moral strictures into public policy, e.g., to roll back gay rights and "crack down" on criminals.

187 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

Without a theoretical framework that pulls all these seemingly disparate behaviors together — as functionally related elements of the authoritarian's classic defensive stance — contemporary analysts can be left puzzling over (for example) why support for the death penalty and for the public whipping of "sex criminals" should turn out to be the strongest "predictors" of a vote in favor of Brexit (Kaufmann 2016). The authoritarian dynamic offers such a framework, which here we will test using recent EuroPulse data on pop-ulist voting across the US, UK, and France.

DATA: EUROPULSE DECEMBER 2016

The EuroPulse survey is conducted each quarter by Dalia Research (Germany). Dalia uses a proprietary software platform to reach respondents through web-enabled devices as they interact with a wide range of websites and apps. Dalia seeks out users fitting the required profile for the task and offers them access to premium content in exchange for survey completion.[2] This should reach a more representative slice of the relevant population and interview them under more natural conditions than is possible (for example) issuing email invitations to that atypical portion of a population that has sufficient interest, time, and energy to register for research panels and complete surveys on any topic for modest material rewards.

188 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

One of the world's largest omnibus surveys, EuroPulse is conducted across all twenty-eight EU countries, in twenty-one different languages. Four times a year, the EuroPulse survey interviews a census representative sample of 10,000 Europeans to track public opinion on a variety of topics. In the unique instance of the EuroPulse survey conducted over December 2-11, 2016 — just a few weeks after US voters elected President Trump on November 8 — Dalia added a representative US sample to the EuroPulse mix. Their stared pinpose was to enable researchers to detect any commonalities in populist support across the US and Europe (including voting for Brexit in the UK and for the National Front in France), publicly issuing a "Research Challenge" to that effect.

The EuroPulse-plus-US data set of December 2016 included 12,235 respondents: n=1,052 in the US sample, and n=11,283 across the European Union. However, given the nature of our research questions, we excluded non-whites from the current investigation, leaving n=661 in the US (which also excluded Hispanics) and n=10,500 across the EU. As explained elsewhere (Stenner 2005), this is not to say that authoritarianism is necessarily expressed in a fundamentally different manner depending on race/ethnicity, or majority/minority status, than among whites across Europe and the US. It is just that the demarcation of ingroups and outgroups, and delineation of the norms

189 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

and authorities to which one owes allegiance, might vary. We would not expect, for example, any authoritarianism among African-American leaders of the Black Lives Matter movement to propel them toward a vote for Donald Trump, nor North African Muslim immigrants in France to be attracted (by any predisposition to authoritarianism) to the National Front. Excluding non-whites left us a sample of 11,161 respondents from twenty-nine countries, with 3,202 of those of special interest in our present search for a common dynamic in populist voting across the US (n=661), UK (n=1,256), and France (n=1,285).

The dependent variable throughout our analyses — our principal outcome of interest — was the probability of voting for populist candidates and causes. For the US sample, this was reflected by respondents' self-report (in early December) of having voted for Donald Trump in the presidential election just a few weeks prior. For the UK, the dependent variable was respondents' self-report of having voted a few months earlier in the British referendum of June 23 in favor of leaving the European Union. For our French sample, populist voting was indicated by self-reports of intended vote in the upcoming election, which would be the presidential election of April/May 2017.

There is mostly good correspondence between these self-reports and the real incidence of both vote turnout and vote choice in these elections, although our starting sample does seem to over-represent Americans who turned out to vote,

190 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

and to under-represent Britons voting to leave the European Union, probably due to some combination of selection and social desirability bias (Karp and Brockington 2005). Survey respondents are disproportionately likely to vote, and people tend to over-report engaging in civic behaviors such as voting. Similarly, it may be that those groups that leaned toward exiting Europe were disinclined subsequently to broadcast that, as well as generally less disposed to answering surveys.[3]

In any case, only those who said they voted (or intended to vote, in the case of France) were retained in the following analyses, leaving final sample sizes of 451, 858, and 1,045 for the US, UK, and France, respectively. Our dependent variable was scored "1" for a vote in favor of Trump, Brexit, or Le Pen, and "0" otherwise. We analyzed each of these three vote choices separately, since they reflect very different decision contexts. But we synthesized our findings across the three countries, since our main goal was ultimately to identify commonalities in the forces driving populist voting across liberal democracies.

We followed our previous practice in forming a "bare hones" measure of authoritarianism from respondents' choices among pairs of child-rearing values. As always, we sought a measure that reflected something more akin to a deep-seated, enduring political "personality" than a current policy attitude; that could do so across widely varying cultures with different ingroups and outgroups, dissidents and deviants; and that did not make specific reference to objects, actors, or events that featured in current political contests and might be the very subjects of our inquiries.

191 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

We formed our measure of authoritarian predisposition from responses to the following four EuroPulse items: "Which is more important for a child to have? Independence / Respect for elders? Obedience / Self-reliance? Consideration for others / Good behavior? Curiosity / Good manners?" Responses considered authoritarian (each scoring "1") were respect for elders, obedience, good behavior, and good manners. Alternatively, preference for children being independent, self-reliant, considerate, and curious reflected the inverse of authoritarianism (each scoring "0").[4] Any inability or refusal to choose between a pair of values ("don't have an opinion") was considered a neutral response (scoring "0.5"). After summing these four components, re-scoring the resulting scale to be of one-unit range, and centering its midpoint on "0" (to ease interpretation of interaction coefficients), our final measure of authoritarian predisposition ranged across nine points from -0.5 to +0.5.

According to this measure, about a third of white respondents across these twenty-nine liberal democracies proved to be authoritarian to some degree, in the sense of passing the neutral midpoint of the scale and leaning toward authoritarianism in their value choices. Specifically, 33 percent were authoritarian, 37 percent were non-authoritarian, and 29 percent were "balanced" or neutral.[5]

192 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

We constructed an overall measure of "normative threat" from several key sentiments found in the EuroPulse survey. We sought to reflect three core components of threat to the normative order: loss of societal consensus, loss of confidence in leaders, and loss of confidence in institutions.

First, the closest sentiment we could find in the EuroPulse survey to perceived loss of consensus was the express feeling that one's country was "going in the wrong direction" (either "very wrong or "somewhat wrong") in response to the question "Over the past 5 years, has the [United States / the United Kingdom / France] gone more in the right or wrong direction?"

Second, we measured general loss of confidence in leaders by means of strong agreement with the statement "Government is controlled by the rich elite," which readers might recognize as an item sometimes deployed in measures of populism. (Recall our earlier assertion that so-called populist sentiments might more simply be understood as perceptions of normative threat.)

Third, we wanted to measure loss of confidence in government institutions in a way that captured both dissatisfaction with the current government and disillusion with democratic government more generally. To this end, we combined ordinal scale responses to two questions: "How satisfied are you with the way democracy works in your country?' (which ranged across four points from "very satisfied" up to "not at all satisfied"), and "What is your opinion of the government in [the United States / the United Kingdom / France]?/" (which ranged across five points from "very positive" to "very negative"). Summing these two equally weighted components created a finely graduated nineteen-point measure reflecting "dissatisfaction with democratic government."

193 - CAN IT HAPPEN HFRE?

Finally, our overall measure of normative threat standardized and summed these three equally weighted components and re-scored the result to he of one-unit range. This overall scale (deployed in all subsequent analyses) ranged across seventy-five points from "-.5" to ".5," centered on a midpoint of "0."

An adequate test of the explanatory power of the authoritarian dynamic in this domain must necessarily also control for the economic "distress" that is traditionally cited as fueling populist sentiments and voting behavior. A number of scholars have noted recently that economic factors actually seem rather weak and inconsistent predictors of populism and intolerance, particularly compared with value conflict and cultural "backlash" (see Inglehart and Norris 2017). Stenner (2005) previously found that, to the extent that economic factors did predict expressions of intolerance, the effect tended to be confined to negative retrospective evaluations of the national economy, which might be felt as a kind of collective threat by authoritarians (although the effects of such threats were rarely as powerful or consistent as the classic normative threats). In contrast, Stenner found that personal economic distress tended to either be inconsequential or actually diminish the impact of authoritarianism on intolerance, perhaps by distracting authoritarians from their problematic concern with the fate of the collective, thereby "improving" their behavior.

194 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

Fortunately, the EuroPulse survey measured the standard array of economic evaluations, including four items asking for retrospective and prospective evaluations of both the national economy and one's own household finances, as follows:

195 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

As noted, these discrete evaluations (whose pairwise correlations here ranged from .20 to .54) have typically been found to exert varying influence on intolerant and populist sentiment, and were thus left as separate variables in our model.

We employed logistic regression to analyze each of our dichotomous measures of populist voting as a function of the authoritarian dynamic — the interaction of authoritarian predisposition with our overall measure of normative threat.

Note that each of these models also originally included as controls the four discrete items reflecting economic evaluations, as well as the interactions of those evaluations with authoritarianism. With sample size trimmed by the elimination of non-whites and non-voters, it was important not to overload the models, particularly in view of their estimation via logistic regression. Thus, if any of these evaluations or their interactions proved statistically insignificant, they were removed from the model in question. The full models and raw results (logit coefficients) from which the findings presented here in the text arc derived are reported in Appendix F, Table 1, at www.KarenStenner.com under "Repository"

196 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

(including results for the economic control variables). The conditional coefficients (marginal effects) calculated from those raw results are also reported there in Appendix F, Table 2.

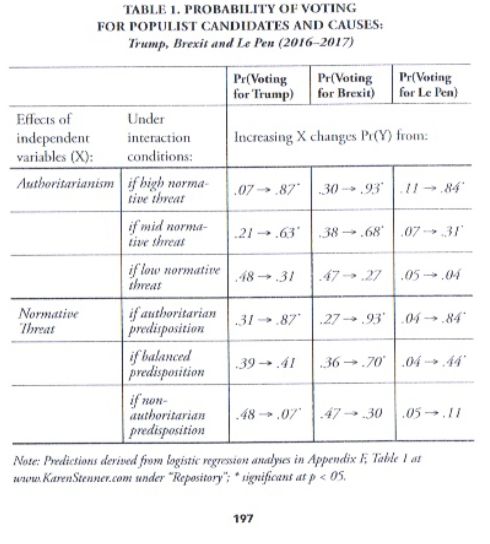

Here in the text itself, we present succinctly in Table 1 (below) only our core findings regarding the impact of the authoritarian dynamic, as conveyed via changes in the predicted probability of voting for populist candidates and causes, given different predispositions to authoritarianism, and varying conditions of normative threat.

197 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

Before turning our focus to the authoritarian dynamic, we note first that authoritarianism did indeed prove to be the main "background" determinant of populist voting across all three countries in our investigation. That is to say, there was no socio-demographic variable whose impact on populist voting exceeded that of our basic "child-rearing values" measure of authoritarianism: not education, income, religion, gender, age, or urban/rural residence. We found that the impact of authoritarianism was substantial even under ordinary conditions — among those not feeling particularly threatened (or reassured) — increasing the probability of a populist vote by about .42, .30, and .24 in the US, UK, and France, respectively (see Appendix F, Table 2, upper panel).

Put more simply, even given middling perceptions of normative threat in their polity, Americans ranged from about a .21 to a .63 probability of voting for Trump as authoritarianism went from its lowest to its highest levels (see Table 1, page 197). Similarly, highly authoritarian Britons had about a 68 percent likelihood, and their non-authoritarian peers about a 38 percent chance, of voting to leave the European Union when perceptions of normative threat were unremarkable. And under those same conditions, about 31 percent of highly authoritarian French voters would likely opt for Le Pen, compared to only about 7 percent of their non-authoritarian compatriots.

198 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

Note that all the statements directly above simply represent alternative ways of describing the results presented in the upper panel of Table I (page 197), across the row labeled "if mid normative threat." This seems the appropriate place to pause and ensure we have clarity first on some important issues of methodology and terminology. For us, the "impact" of any independent variable (e.g., authoritarianism) is the difference in expected outcomes (e.g., in the likelihood of voting for Trump) between those scoring at the extremes (highly authoritarian versus non-authoritarian) of that explanatory variable. Technically, it is the change predicted in the dependent variable for a one-unit increase in the independent variable, e.g., the change in the probability of populist voting in response to a one-unit increase in authoritarianism. Recall we scored all our variables such that a "one-unit increase" always entails moving across the full range (from lower to upper bound) of the explanatory variable, e.g., it is the difference between the very non-authoritarian and the highly authoritarian. The change that such an increase induces in the likelihood of populist voting is, in our terminology, the "impact" of that explanatory variable.

Crucially, we expect that this impact will vary under different conditions, e.g., given conditions of normative threat or reassurance. This varying impact is reflected by the varying magnitude and direction of the conditional coefficients we report in Appendix F, Table 2, and likewise by the steepness and direction of the slopes in the associated Figures 2 and 3 (below). The reader can refer to Appendix F, Table 1 for the full results from which these conditional coefficients and slopes were derived.

199 -CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

200 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

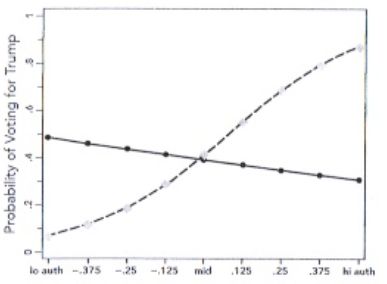

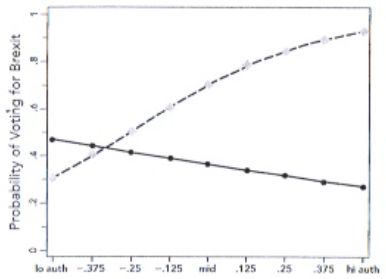

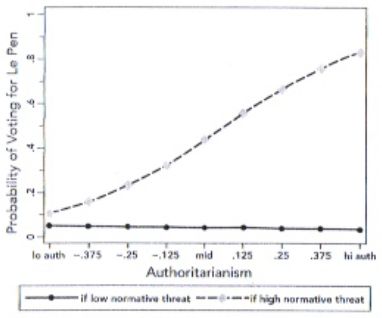

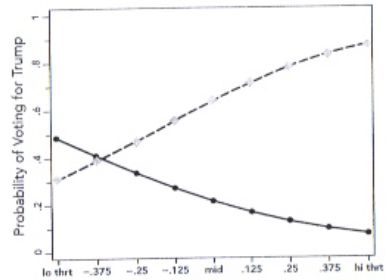

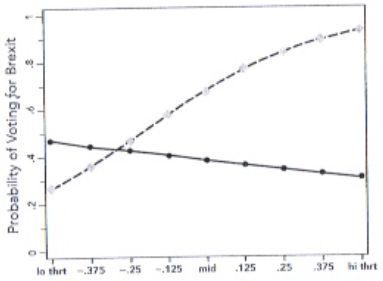

Figure 2 (opposite) depicts the impact upon voting for populist candidates and causes of moving across the full range of the authoritarianism measure (from very non-authoritarian up to highly authoritarian) as the variable with which it interacts — normative threat — is held, in turn, at very high and low levels. These different slopes graphically reflect what we have called the authoritarian dynamic: they represent the varying effects of authoritarianism under conditions of normative threat and reassurance.

The three constituent panels of Figure 2 reflect the probability of voting for Trump, Beak, and Le Pen, respectively. All these authoritarianism x normative threat interactions proved to be very substantial and highly significant (see Appendix F, Table 1). As anticipated, the impact of authoritarianism was greatly magnified (steepened) under conditions of normative threat. For example (see Figure 2, upper panel), we found that authoritarianism increased the probability of voting for Trump by about .80 under conditions of high normative threat, with the likelihood of a Trump vote ranging from only about 7 percent (for non-authoritarians) to about 87 percent (for authoritarians) among disillusioned respondents who saw their government as controlled by rich elites and their country headed in the "wrong direction." Note that the steepness of these slopes and their end points (both specified above) align, respectively, with the marginal effects reported in Appendix F, Table 2, and with the marginal probabilities presented here in Table 1 (page 197).

201 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

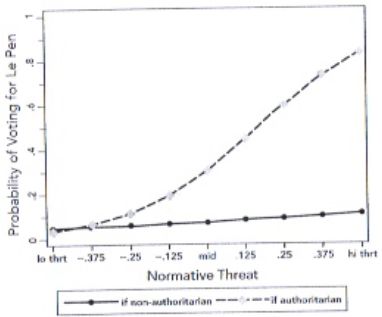

Much the same pattern was evident for the UK (see Figure 2, middle panel), where we found that authoritarianism increased the probability of voting to leave the European Union by about .64 given conditions of high normative threat, with the likelihood of favoring Brexit ranging from about 30 percent (for non-authoritarians) to about 93 percent (for authoritarians) when leaders, governments, and democracy itself were all found sorely wanting (see Table 1, page 197). Likewise regarding the electoral appeal of the National Front in France (see Figure 2, lower panel). Here we found that authoritarianism increased the probability of voting for Le Pen by about .75 given high normative threat, with the likelihood of a vote for the National Front ranging from about 11 percent (among non-authoritarians) to about 84 percent (among authoritarians) given wholesale loss of confidence in democratic government and leadership (see Table 1, page 197).

Notice that throughout Figure 2, this impressive impact of authoritarianism is effectively flattened to virtually nothing under conditions of great normative reassurance, i.e., when people are sure their country is headed in the right direction and feel confident in the workings of democracy, positive about the government, and unconcerned about elite machinations. Although the marginal effects are not statistically significant in the case of reassurance, we see at least a hint in these pictures that under these reassuring societal conditions, authoritarians might even be repelled by populist movements, seemingly lending more of their support to mainstream parties and leaders when the normative order seems intact and functional, and worthy of their allegiance.

202 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

Keep in mind it is not that people become less authoritarian under these conditions, only that their authoritarianigm produces less manifest intolerance. Their inherent predispositions remain intact but latent, awaiting only the sounding of the next societal alarm — about immigrant hordes, moral decay, political disarray — to kick back into action and haul out the defensive arsenal.

Some of this becomes clearer still when viewed from a different angle. Figure 3 (page 204) simply takes that same authoritarianism x normative threat interaction and depicts it from the other side, this rime showing how the impact upon populism of normative threat (of moving from the lower bound of the scale, reflecting great reassurance, up to the upper bound, indicating extreme threat) depends on the predispositions of the perceiver: whether authoritarian or non-authoritarian.

When considered from this alternative perspective, the potential political power of the authoritarian dynamic is readily apparent. In the lower panel of Table 1 (page 197), we see that increasing feelings of normative threat intensified attraction to populism even among those of "balanced" disposition (at least outside the US), who were driven a considerable way toward voting for Brexit and nearly halfway

203 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

204 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

to accepting the National Front as feelings of normative threat soared. But this impact of normative threat on populist voting was basically doubled for those of authoritarian disposition. As anticipated, it was authoritarians — heavily invested in the normative order that fills their world with oneness and sameness — who were by far the most reactive to normative threat (see Figure 3). For example, we calculated that rising normative threat increased authoritarians' probability of voting for Trump by about .58 (see Appendix F, Table 2), boosting their likelihood of a Trump vote from about 31 percent, among those feeling reassured about the polity, up to about 87 percent, for those convinced their world was coming apart (sec Table 1, page 197).

We detected the same Forces at work in the UK sample (see Figure 3, middle panel), where we found that mounting threats to the normative order drove authoritarians toward leaving the European Union, boosting their likelihood of Favoring Brexit from about 27 percent, when feeling roundly reassured, up to about 93 percent, once highly threatened (see Table 1, page 197). An even starker picture was painted for France (see Figure 3, lower panel). Here we saw the accumulation of normative threat increase authoritarians' probability of voting for the National Front by about .80, lifting their prospects of tapping Le Pen for the presidency from as little as 4 percent, given constant reassurance, to as much as 84 percent, in the face of intense normative threat (see Table I, page 197).

205 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

Finally, our evaluation of the evidence is not complete until we consider how normative threat affects those at the lower bound of the authoritarian spectrum. Across two decades of empirical research, we cannot think of a significant exception to the finding that normative threat tends either to leave non-authoritarians utterly unmoved by the things that catalyze authoritarians or to propel them toward being (what one might conceive as) their "best selves?" In previous investigations, this has seen non-authoritarians move toward positions of greater tolerance and respect for diversity under the very conditions that seem to propel authoritarians toward increasing intolerance. In a nutshell, authoritarians act more like authoritarians, and non-authoritarians more like their antithesis, under these conditions. As authoritarians move to shore up their defense of oneness and sameness, non-authoritarians may redouble their own efforts on behalf of the "open society." Based now on this latest evidence, it seems that non-authoritarians' "activation" — in defense of freedom and diversity over obedience and conformity — includes rejection of populist candidates arid causes that fail to share this vision of the good life.

Certainly this appears to hold at least for non-authoritarians in the contemporary United States: see Figure 3, upper panel, for a stark depiction of this "classic" polarization under conditions of normative threat. It is sobering indeed to ponder the self-fueling properties of this dynamic — where perceptions of normative threat produce increasing polarization that in turn further exacerbates normative threat — which is surely implicated in our debilitating contemporary "culture wars" (see also Hetherington and Weiler, 2009).

206 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

The one empirical task that remains is to compare the impact of the authoritarian dynamic on support for populist candidates and causes with that of economic "distress," variously conceived. As noted at the outset, the notion that populist attitudes and behaviors are driven, in some way, by economic distress is one of the most common accounts offered for the current "wave" of populism in the wake of the GFC, the decline of manufacturing, and the inevitable dislocations of globalism. It is a highly "rational" account of the populist phenomenon, with economics and materialism at its core, and analysts offering these kinds of accounts sometimes go to considerable lengths even to reframe manifestly nonmaterial explanations in materialistic terms. For example, there is the argument that anti-immigrant sentiment is not really (or only) about immigration, but instead (or additionally) a means of expressing economic fears and displacing them onto the immigrants (refugees, minorities, guest workers, terrorists-in-the-making) who are purportally stealing the natives' jobs and draining communal resources that ought to be reserved for the locals.

Our own investigation finds the evidence in support of the notion that populism is mostly fueled by economic distress to be weak and inconsistent, however that distress is conceptualized. Preliminary analyses confirmed that the four economic evaluations available in the EuroPulse data (retrospective and prospective evaluations of the national economy and household finances) represented distinct sentiments, and ought to be entered separately in our model.

207 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

In terms of both the magnitude and direction of their effects, these four variables exerted widely varying influence on populism (in contrast to the various components of normative threat), as a review of the economic results in Appendix F will confirm. This persisted even without controlling for authoritarianism and normative threat, and regardless of whether the model included interactions between authoritarianism and the various economic components.

We found that the effects of these economic evaluations were either weak and inconsistent or, sometimes, large and counterintuitive. Evaluations of household finances seemed mostly inconsequential as predictors of populist voting (which accords with the generally modest effects discerned for income). Perceptions of (past) national economic decline had some mixed effects (including, in the case of France, in interaction with authoritarianism), but certainly seemed to propel some voters toward Trump. Yet even that finding sits side by side with a seemingly counterintuitive result, with positive evaluations of the economic future apparently associated with support for both Trump and Brexit (see Appendix F). Of course, the direction of causality remains unclear. Given that these hopeful sentiments were measured after the vote in each case, it is quite possible that having voted for Trump/Brexit, these voters consequently felt more optimistic about the future. It is plausible that a vote for Trump may have reflected in some part dissatisfaction with past economic progress together with hope for a future economic turnaround. if so, this would make America's choice of a billionaire businessman for president an expression not just of unleavened economic fear and disappointment but also at least a touch of economic hope and optimism for the future.

208 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

In any case, what we found is that there is no real pattern to be discerned in regard to economic influences across either the different economic components or the different politics. This would accord with the inconsistent findings typically reported by others, and with the general state of uncertainty regarding whether we are truly confronting a "wave" of populism (and whether it is surging or has stopped), and also with the continuing disagreement over the direction of causality between anti-immigrant sentiment and professions of economic distress. We refer here to the dispute over whether our "populists" are typically starting with (real or imagined) perceptions of financial/economic threat and projecting that onto easy targets like immigrants, or whether they are starting with their opposition to immigration and — due to the constraints of political correctness — merely expressing that as economic distress (viz., "the immigrants are stealing our jobs"). We think the totality of evidence tends to favor the latter, a theme we will return to below.

Trump ascended to the American presidency, Britain exited Europe, and the French flirted with the National Front because Western liberal democracies have now exceeded many people's capacity to tolerate them — to live with them, and in them. This is hard to accept until one comes to terms

209 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

with two critical realities. First, people are not empty vessels waiting to be filled with appreciation and enthusiasm for democratic processes. It is perhaps ironic that tolerance of difference is now threatened by liberal democrats' refusal to recognize that many of their fellow citizens are . . . different. We all come into the world with distinct personalities, which is to say, predisposed to want, need, and fear different things, including particular social arrangements. Presumably, societies with a diverse mix of complementary characters tended to survive and adapt to changing environments in human evolution. Notwithstanding some ancient migration bottlenecks, these different personalities — authoritarian and libertarian, open and closed, risk-seeking and risk-averse, to name but a few — have over time distributed themselves all around the world. This means there are plenty of would-be liberal democrats languishing in autocracies, and many authoritarians struggling along under "vibrant" liberal detnocracies.

Second, there is remarkably little evidence that living in a liberal democracy generally makes people more democratic and tolerant. This means that most societies — including those "blessed" with democracies — will persistently harbor a certain proportion of residents (by our calculations, roughly a third) who will always find diversity difficult to tolerate. That predisposition, and those limitations, may be largely immovable. And this is the most important implication: if we are right about normative threat serving as a critical catalyst fin these characters, then the things that multiculturalists believe will help people appreciate and thrive in democracy-

210 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

experiencing difference, talking about difference, displaying and applauding difference — are the very conditions that encourage authoritarians not to the heights of tolerance, but to their intolerant extremes. Democracy in general, and tolerance in particular, might actually be better served by an abundance of common and unifying rituals, institutions, and processes.

Democratic enthusiasts and multiculturalists sometimes make the mistake of thinking we are at an enlightened point in human history (Fukuyama 1992) when all these different personalities daily experiencing the joys of increasing liberty and democracy — are evolving in a fairly predictable and linear fashion into more perfect democratic citizens. This is why the populist "wave" strikes many observers as a momentary madness that "comes out of the blue," and why the sentiments that seem to fuel these movements are ofien considered merely the products of frustration, hatred, and manipulation by irresponsible populist leaders — certainly not serious, legitimate prefrences that a democracy must attend to.

When authoritarians raise concerns about, say, the rates or sources of immigration, they are not actually saying, "I'm scared I might lose my job," but in fact, "This is making me very uncomfortable and I don't like where our country is headed." Moreover, "Nobody will let me say so, and only [this Trump-like figure] is listening to me." Our sense is that if Trump had not come along, a Trump-like figure would have materialized eventually. It may be the case that many Republicans would have voted for anyone marketed under

211 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

the Republican brand. And Hillary Clinton may well have won if FBI director James Comey had not made his ill-timed announcement. And it seems likely that Russian interference tilted the outcome. But one must still explain why a Trump-like figure was even within reach of the presidency, and why Trump-like figures are popping up all over, and why the outrageous statements that critics thought would surely destroy their candidacies seem to be the very things that most thrill their supporters and solidify their bases.

Trump publicly inviting Russia to hack into Clinton's private emails was shocking to many from a number of perspectives, but perhaps the most prominent was the lack of horror expressed by many of his supporters at what might conceivably be characterized as treason. When being interviewed about his foreign policy, Trump assured us that he himself would happily "take out the families" of suspected ISIS terrorists: essentially, making a public declaration of his willingness to commit war crimes. Far from provoking horror, Trump's many astonishing statements — all indelibly infused with classic authoritarian sentiments

and stances — were greeted with a kind of exhilaration by his supporters. It became clear that a large portion of the American people felt the nation's political leaders had not just failed them but actually did not represent them. Here "represent" goes well beyond mere political representation to something more primitive, like "belonging." In essence: "You are not us." In this state of mind, it no longer seemed beyond the pale to publicly invite a dangerous and long

212 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

standing adversary to spy on the country's leaders, or extol the effectiveness of war crimes for nipping terrorism in the bud. The gleeful reactions of Trump's supporters to his "strongman" posturing attested to their anger and bitterness regarding the "political correctness" of the "liberal elite," and the pleasure they seemed to derive from watching someone who sounds like "us" finally sticking it to "them."

Clearly, immigration policy is the flashpoint for populism and offers a critical starting point for any new efforts at civil peace. If citizens say they're concerned about the rate of immigration, we ought to at least consider the possibility that they're concerned about the rate of immigration, and not merely masking a hateful racism or displacing their economic woes onto easy scapegoats. Common sense and historical experience tell us that there is some rate of newcomers into any community that is too high to be sustainable — that can overwhelm or even damage the host and make things worse for both old and new members. It is also common sense that some newcomers are more difficult to integrate than others — especially when there are clashing values and lifestyles. Some might, accordingly, need to be more carefully selected, or more heavily supported and resourced to encourage and aid their assimilation. All these things must he considered when formulating a successful immigration policy (Haidt 2016). Ignoring these issues is not helpful to either the hosts or the newcomers. It is implausible to maintain that the host community can successfully integrate any kind or newcomer at any rate whatsoever, and it is unreasonable to assert that any ether suggestion is racist.

213 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

As noted, we already have some idea of what the requirements for social cohesion are in many other contexts. There are surely types and degrees of affinity between host and newcomers, rates of entry, and methods of supporting their assimilation and inclusion that facilitate successful integration into the community. Frank consideration of these matters is the key to broad acceptance of immigration policy and vital to the continued health of our liberal democracies. For all the reasons we have canvassed, these things are not currently known, but are knowable. It is essential for free societies to discuss these issues openly, and a matter of great urgency that we empirically investigate these parameters and settle the matter with hard evidence. Most obviously, if we were able to discuss these kinds of questions openly, they could simply be incorporated into mainstream political debates and effectively managed by normal political processes, cutting much of the fuel for intolerant social movements. Another important benefit of better immigration policies is that the resulting improvements in social inclusion and cohesion are likely to reduce the prospects of radicalization and terrorism, since these phenomena may be driven, in large part, by the dis-integration of perpetrators from their families and communities.

214 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

Although we have paid great attention here to the role played by normative threat in the populist phenomenon, one critical thing to note about authoritarians is that they are not especially inclined to perceive normative (or indeed, any other kind of) threat — they are just especially reactive when they do. If anything, authoritarians, by their very nature, want to believe in authorities and institutions; they want to feel they are part of a cohesive community. Accordingly, they seem (if anything) to be modestly inclined toward giving authorities and institutions the benefit of the doubt, and lending them their support until the moment these seem incapable of maintaining "normative order." As our observation of the mechanics of the authoritarian dynamic made clear, authoritarians are highly reactive and highly malleable. Depending on their assessment of shifting environmental conditions, they can be moved from indifference, even positions of modest tolerance, to aggressive demands to "crack down" on immigrants, minorities, "deviants," and dissidents, employing the full force of state authority. This is to say, the current state we find ourselves in can easily be made much worse, or much better, by how we come together and respond to this now in terms of attending to people's needs for oneness and sameness; for identity, cohesion, and belonging; for pride and honor; and for institutions and leaders they can respect. This should take the place of demeaning and ridiculing authoritarians, ignoring their needs and preferences (which

215 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

is an undemocratic way for a democracy to treat a third of its citizens), and simply waiting for them to "come back to their senses." It is condescending to say that no sane, reasonable person could want the things they want, therefore they must be unhinged or else arc being manipulated. But this is no momentary madness. It is a perpetual feature of human societies: a latent pool of need that lurks just beneath the surface and seems to be activated most certainly by things that constitute the very essence of liberal democracy — things such as

. . . the experience or perception disobedience to group authorities or authorities unworthy of respect, nonconformity to group norms or norms proving questionable, lack of consensus in group values and beliefs, and, in general, diversity and freedom "run amok". . . (Stenner 2005: 17).

Liberal democracy has now exceeded many people's capacity to tolerate it. And absent proper understanding of the origins and dynamics of this populist moment, well meaning citizens, political parties, and governments are likely to respond to these movements in ways that serve only to exacerbate their negative features and entirely miss their possibilities. The same warning goes out to all of Western Europe and the English-speaking world post Brexit. Worst of all, we might miss the real opportunities for a thoughtful, other-regarding reconciliation of two critical parts of our human nature: the desire to liberate and enable the individual, and the impetus to protect and serve the collective.

Page 216 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

We have shown that the far-right populist wave that seemed to "come out of nowhere" did not in fact come out of nowhere. It is not a sudden madness, or virus, or tide, or even just a copycat phenomenon — the emboldening of bigots and despots by others' electoral successes. Rather, it is something that sits just beneath the surface of any human society — including in the advanced liberal democracies at the heart of the Western world — and can be activated by core elements of liberal democracy itself.

Liberal democracy can become its own undoing because its core elements activate forces that undermine it and its best features constrain it from vigorously protecting itself. So it seems we are not at the "end of history" (Fukuyama 1992). 'the "last man" is not a perfected liberal democrat. Liberal democracy may not be the "final form of human government." And intolerance is not a thing of the past; it is very much a thing of the present, and of the future.

Adorno, Theodor, Else Frenkel-Brunswik, and D, J. Levinson. 1950, The Authoritarian Personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Albertazzi, Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell. 2008, Twenty-First Century Populism. The Spectre of Western European Democracy. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan.

Duckitt, John. 1989, “Authoritarianism and Group Identification: A New View of an Old Construct,” Political Psychology, 10(1): 63-84, Fukuyama, Francis. 1992, The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

Page 217 - CAN IT HAPPEN HERE?

Haide, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books 7 - 2016. “When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism.” The American Interest, 12:1, July 10.

Hetherington, Marc J., and Jonathan D. We iler. 2009. Authoritariansim and Polarization in American Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Nortis. 2016. “Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash." HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026.

Karp, Jeffrey A., and David Brockington. 2005, "Social Desirability and Response Validity: A Comparative Analysis of Overreporting Voter Turnout in Five Countries." Journal of Politics, 67(3): 825-40.

Kaufmann, Eric. 2016. “Brexit Voters: NOT the Left Behind.” Fabian Review, June 24.

Ludeke, Steven, Wendy Johnson, and Thomas J. Bouchard, Jr. 2013. "Obedience to traditional authority”: A heritable factor underlying authoritarianism, conservatism and religiousness. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(4): 375-80.

McCourt, K., Bouchard, T. J., Jr., Lykken, D. T., Tellegen, A., and Keyes, M. 1999. “Authoritarianism revisited: Genetic and environmental influence examined in twins reared apart and together.” Personality and Individual Differences, 27: 985-1014.

Mudde, C, 2004, The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39: 541-63.

Mudde, C., and C. R. Kaltwasser. 2017, Populism: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stenner, Karen. 2005. The Authoritarian Dynamic. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

— “Three Kinds of ‘Conservatism.'" Psychological Inquiry 20,

no. 2/3 (April-September 2009a): 142-59.

— "'Conservatism,' Context-Dependence, and Cognative

Incapacity.” Psychological Inquiry 20, no. 2/3 (April-September

2009b); 189-95.

Page 218 - AUTHORITARIANISM IS NOT A MOMENTARY MADNESS

1. ‘This section draws on arguments and evidence first presented in Stenner (2005, 2009a, 2009b). The reader is referred to the originals for further details and discussion.

2. In terms of collection methodology, Dalia’s platform approaches millions of potential respondents through a network of over 40,000 apps and websites, whose users are anonymously profiled across key demographic attributes and selected according to census statistics. Data are collected online via desktop, laptop, cablet, and smartphone, and then weighted according to population struccures and census statistics to obtain a representative sample.

3. Ultimately, just 55 percent of eligible Americans actually voted in the 2016 presidential election (compared co the 68 percent of our US sample who reportedly turned out), with 46 percent of those voting for Trump (compared to 44 percent in our sample). In Britain, 72 percent of those registered turned out to vote in the referendum, which exactly matches our British sample's self-reported turnout. But as noted, our sample seems to underrepresent the “exit” vote, with 52 percent voting, to leave the European Union in reality, compared to 43 percent in our sample. Our figures do closely align in the French case, where 78 percent of those who were eligible voted in the first round of the recent presidential election (compared to the 80 percent of our French sample who said they intended to vote). And 21 percent ultimately opted for Le Pen in that first round (compared to the 22 percent of our sample who said they intended to do so).

4. Note that this is simply an unobtrusive means of measuring values; it need not reflect either how respondents were raised or how they are raising their own children.

5. We stress that the people we classified as being of authoritarian predisposition did not always describe themselves as right of center. In fact, when required to “describe [their] political views on a left-right scale,” 42 percent of these authoritarians chose one of the “left-wing” options, while 58 percent chose one of the right- wing options. Among those we classified as non-authoritarian, 55 percent placed themselves left of center and 45 percent placed themselves right of center.

Page 219

Dr. Karen Stenner - @karen_stenner

Political psychologist & behavioral economist, best known for long ago predicting the rise of Trump-like figures under the kinds of conditions we now confront.

www.karenstenner.com/

Jonathan Korman - @miniver

user experience strategist • hermeticist • soixante-huitard • nerdy & geeky • against fascism • flinty optimism • he/they: http://mastodon.social/@Miniver

1/2/2021

Source https://9bb6f4fe-ee8e-4700-aaa9-743a55a9437a.filesusr.com/ugd/02ff25_370d387d81714d29bad957ba03cf8e48.pdf